Monitoring Natural and Induced Seismic Events

Since 2013, we have installed more than a dozen seismic stations in Alberta, mainly in areas where earthquake activity has increased. These stations form our seismological network: the Regional Alberta Observatory for Earthquake Studies Network (RAVEN). Over this same time-period, we forged partnerships with other organizations creating robust seismic monitoring capabilities within the province. We are receiving data from over 100 seismic stations operated by eight seismic monitoring networks in Canada and the United States.

More About Monitoring Earthquakes

A considerable density of seismic stations is critical for an effective earthquake monitoring system. Building a dense network of both telemetered (transmitting real-time data) and offline stations increases the sensitivity of earthquake recordings in the province. It improves the reliability of locating events—the greater the density of seismic stations, the smaller the earthquakes detected and located.

The federal government started monitoring earthquakes in Canada in the late 1800s. By the 1950s, the federal seismological network could detect earthquakes of magnitude 6 and larger throughout Canada. Adding two Alberta stations and several British Columbia stations (e.g., Suffield, Edmonton, and Waterton stations) during the 1950s and 1960s allowed us to detect hundreds of smaller earthquakes in southwestern Alberta. It was not until the mid-2000s that the seismic monitoring capacity across Alberta substantially improved when the University of Alberta installed the Canadian Rockies and Alberta Network (CRANE) consisting of more than 20 seismic stations across the province.

Learn More About:

We deployed our first two seismic stations in 2013, followed by seven additional stations in 2014, which formed the basis for the Regional Alberta Observatory for Earthquake Studies Network (RAVEN). The RAVEN stations send data about local earthquakes and moderate or larger worldwide earthquakes in real-time using satellite and cellular technology. The RAVEN now accommodates 19 seismic stations around the province, concentrated in areas of increased earthquake activity.

Seismic Station Design

The design and set-up of a seismic station is important to its longevity and continuous functionality. Our typical seismic station consists of two barrels buried underground, containing electronics such as a seismometer, digitizing equipment, communications equipment, and four deep-cycle rechargeable 12-volt batteries. This setup ensures the station has maximum protection from extreme weather fluctuations and water damage to sensitive electronic equipment.

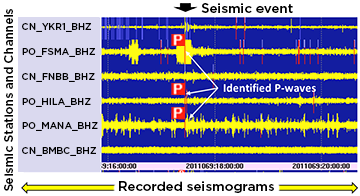

The components of the seismic station work together delivering seismic data to our experts. The seismometer is the heart of every station and detects ground movement caused by incoming seismic waves (P, S, and surface waves) from an earthquake. A digitizer then converts this recording to a digital signal, which is consistently and reliably transmitted in near real-time to our research facilities. Solar panels power the entire station. Our seismologists analyze this transmitted data, identifying seismic events and building an earthquake catalogue for the province.

Learn More About:

We enhance our provincial seismic monitoring network, RAVEN, by building partnerships and sharing data with other jurisdictions and organizations monitoring seismic activity in or surrounding our province. Through these partnerships, we receive data from over 100 seismic stations located in Canada and the United States. These stations are part of eight seismic monitoring networks:

- Regional Alberta Observatory for Earthquake Studies Network

- Canadian National Seismograph Network

- Alberta Telemetered Seismograph Network

- Canadian Rockies and Alberta Network

- TransAlta Dam Monitoring Network

- Northeast British Columbia Network

- Montana Regional Seismograph Network

- United States National Seismic Network

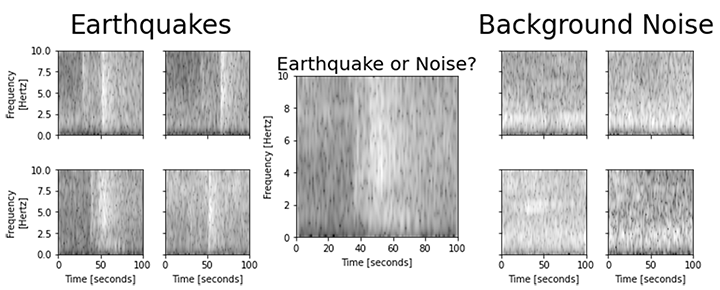

Our seismic station network detects ground motion generated by the natural environment and human activity, not only ground motion from earthquakes. For example, the stations will pick up ground motion from a large truck driving by a station or from a rockslide occurring nearby. It can be difficult to distinguish a small earthquake from these other sources of ground motion. Since we want to detect small earthquakes, our seismologists are working on implementing a system that uses machine learning to find the earthquakes amongst all the seismic recordings. To do this, we show the machine-learning model examples of identified earthquake and non-earthquake events, teaching it that non-earthquakes are background noise. Once the model learns the difference between an earthquake and background noise, it will bring potential earthquake recordings to the seismologists’ attention. This machine-learning model will greatly reduce the time our seismologists spend sifting through all the seismic recordings to find earthquakes.